William Burroughs once said that heroin addicts, although they are all around us, and in fairly large numbers — are invisible — that they slowly fade from normal sight. Their Chakras are all jammed, and so render them see-through. This is how they move among us without being seen. They gradually lose all definition and change shape and consistency until they are anonymous and un-noted. Likewise a mysterious bird described by Tennessee Williams in The Fugitive Kind — a bird no bigger than your fist that has invisible wings and no feet. It eats on the wing, sleeps on the wing and mates on the wing — it touches down only once —and that is to die. A marvellous creature which can never be seen. As a survival strategy it is admirable — allowing them to exist, even to thrive — without ever calling overt attention to themselves. The bird cannot be seen by its enemies — and it is true that when you do spot a heroin addict there is a sense of real surprise. So it is in art. There is a path less travelled — surely not that of the addict (but which also abandons itself easily to states of reverie) — but just the same sends out disinformation in the guise of the familiar, the vernacular, the average and the typical — causing an odd interchange of information — an autistic jumble that confounds and puzzles — but at the same time goes unnoticed — vampire in the night — seeming for all the world unexceptional and not especially impressive. But they pass just the same — you let them into your consciousness because they appear so normal, so unremarkable. These objects can be silly yet stealthy, jarring yet ambient — they're set on 'silent running' and slip in between the cracks and fissures that make up the world of logical objects. These are objects turned slightly in on themselves — not very demanding — but unusually poetic. They are often elliptical — having multiple meanings and no one 'right' answer. They speak softly but they carry a big stick — they have almost no bark, but possess a stinging bite. If these objects could speak they'd probably mumble. Full of potential energy — you have to rouse them from their somnambulent camouflaged state. There is a real ebb and flow to this art — just when you think you're getting one thing, something else begins forming on your screen. This is an art which jams your Chakras — causing all sorts of unusual effects.

This is a genus of object that has no name and is difficult to classify — that tells you as much about what it isn't as it does about what it is, or might be. All the works in this show have a kind of Moebious logic — continuous yet convoluted. Elusive yet in-your-face, these objects are almost art, and at the same time only art. A category which slips in and out of craft and folk, primitive and practiced, naïve and highly calculated — these are works which seem like things they're not — and don't seem like the things they are. Seem confusing — well it is — but that's where the wallop is. Often they play with the 'Readymade' or the 'already Known' — so the spirits of Duchamp and Johns are readily summoned. And of course Surrealism. But they hark back to childhood as well, and recollections and early ways of making or seeing or using objects. All three of these artists exploit elliptical psychological slippage — and weave webs between pervious meaning and contaminated rules and regulations. They're aesthetic backsliders who subvert interpretation and quotidian function and make objects which want to be in more than one place at a time. This lets them occupy the high ground of theory, ideas and a kind of 'coolness' while at the same time the low road of humour, banality and playfulness. Their work has an almost impish quality — like there's something lurking inside of each one, something a little nasty or menacing. These are mystery objects left out at the creation and they broadcast wave upon silent wave of dodgy misinformation and illusory distortion. Neither Peter Cain, Michael Jenkins nor Michael Landy are mean as much as they are mischievous.

You think you can size up their works in a glance, and in a way you can. Here's a car, here's a cart, here's a raft — and that's that. But if you walk away after such an initial (and cursory) read — these objects, in a sense, have had the last laugh. It's a little like not getting a joke. Then when you finally do 'get' it - you feel a little embarrassed. These objects speak in a kind of broken English as if they were reluctant to speak at all. Indeed, all three artists' work feels reticent or shy or at least apprehensive about saying too much - and this is really refreshing, coming as it does after so much talkative, even verbose, work in the late eighties. All three artists work with one foot outside language - dubious of our mad rush to 'understand' the world, rather than 'experience' it. They mean to slow you down - get you to loosen up a bit - kick off your high-falutin shoes and simply see again - rather than to keep reasoning everything out. But it's not all fun and games, is it? Each one has a strategic side to him - a part that feels very thought out, even chilling.

Looking at Peter Cain's spliced car parts you can be taken aback at re-recognizing that the image is either upside-down or sideways. You see his work the way you do advertising - you hardly notice it at all - until it is too late. Cain gets you to speak in tongues you didn't know you knew as he collapses together the super-exacting techniques of painterly photo-realism with surrealistic dream objects with the everydayness of the world of the car. His paintings make you know more - to reach further. His pictures are so verifiable, so perfectly rendered, so much from the draftsman's hand. He has the touch of a faun - but a quirky intelligence which borders on the ephemeral. His work sucks you into its dead surfaces, charged with almost day-glo, medium intense colours (I can't quite name these colours) - all feeling fairly artificial yet vaguely life-like. His work wants to be like the careful, almost architecturally obsessive, drawings of cars by adolescent boys - but also the glitzy images from car magazines. But its dead-eyed deadpan accuracy keeps his work hovering out of reach of this more harmless ground and places it in the ethereal air of images of contemplation - mantra like and mesmeric - inspired and pure. These are almost devotional pictures, and bear an odd inkling of the work of Lee Bontecue. Really Cain's work is like high-art - it's involved with mastery and a profound love of looking. It's interesting to think about photography and its influences on recent art while looking at Cain. Photography with its omnipresent eye on the world was used to critique the slippery nature of advertising, art and history. In turn Cain uses it (photography) in order to re-subvert the camera - making paintings of pictures of things which could never be. Cain veers close, in his way, to some of the young German photographers, especially Thomas Ruff. Cain creates a blind spot right in the middle of your vision as you look at things you think you already know and don't - and things you didn't know you knew but now do. And he does this under your very nose.

Meanwhile Michael Jenkins makes quirky, earnest objects that enter the hallowed ground of protected (or repressed) memory. His objects have the same difficult to get to know, implacable distance as Watteau's 'Giles' - who is in the world but not quite of the world. If Jenkins' objects were people they'd have that same outof-step, gentle waywardness - and unassuming captivation as Watteau's innocent, guileless, disinterested stranger, with Jenkins the magic word is 'gentle'. He seems virtually incapable of cynicism or bombastic braggadocio. Jenkins, probably the contemporary 'master of yellow' creates simple everyday objects, but injects them with a dose of realisation and consciousness - which in turn makes one set off into the world of the daydream and the house of recall. He has a serene way with modest materials - you feel an empathy for his work the way you do for certain special people in your life. There's nothing high-tech here, no fancy hardware or Simulationist jazz. This empathy allows you to see his work with your defenses down, and thus a whole squadron of meaning makes it through our downed screens and implants a sad message within your heart. Jenkins' work (unlike Cain's or Landy's) makes the personal into the political. Somehow he gets you to contemplate his quiet sculpture in the light of social sub-text. You know he's trying to tell you something -he's tapping out some kind of secret code - one you could easily miss or misinterpret. All three of these guys make work that you could get really wrong - but that's that original survival strategy. What allows them to drive their respective points home. These pretty yellow objects speak of plague and quarantine, the cast-out and the forgotten, the hated and violated. Jenkins' work sounds a silent echo through you — a reverberation — of all the bad personal news you get over the airwaves, but never know what to do with. He does it for you, speaking in a kind of childish, yet sophisticated cryptic sculptural semaphore — with his gentle heart and gossamer hand.

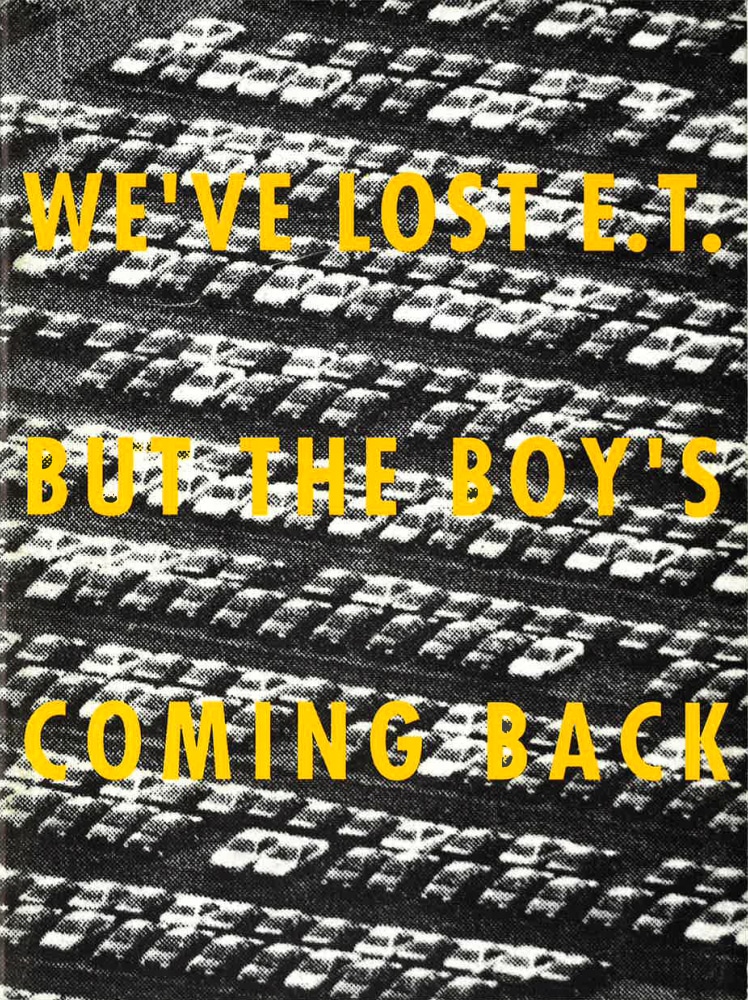

Michael Landy's objects enter the world in disguise (not unlike Cain's) — they're undercover agents working deep — only dressed as clowns — passing for normal in spite of this dose of chromatic steroids he has his objects hopped up on. His objects are like the proverbial 'broad side of a barn' — so big that you can't possibly miss them — but you do. His sculptures are like decoys — only in reverse: instead of blending in or emulating their surroundings Landy's audacious objects do just the opposite — they stand out for all the world to see. They're gregarious and garrulous, but they're also refined and tasteful. Formally alluring — at first you think you're simply passing by some great looking utilitarian antique object (this in contrast to Cain and Jenkins) — some fantastic piece of the world — the kind you wish there were more of, the kind they don't make anymore. Landy simultaneously preserves and destroys the past in his supercharged works. They have cinematic presence — like a vaudeville or silent comedy. There's something distinctly classic about his candy-coloured sculpture. But the punch line can hit you below the belt. This is their insidious side — like they can really sucker-punch you —just when you think they're harmless or oafish or clownlike buffoons. There's a punk strategy at work here — a dismantling, malcontented, malevolence mixed with an activist's mind and a comedian's dark moods. Landy is like a really effective terrorist who is paradoxically nonviolent, yet terribly threatening. His work spares little quarter — he makes it hard to get in — once you establish there is an in to get into. There's a sinewy pugnacious side to his work but with the heart of a caring guy. This is an artist who could really plan a sneak attack.

All three, then, are alike — and of course completely unalike. But grouping them together causes some of their territories to shift somewhat. The Cain remains hermetic, the Jenkins inquisitive and melodic, slowly feeling its way, while Landy hardens and flexes, taunting the space. What do you make of an object that makes itself invisible yet assertive, obvious yet evasive, self-effacing and underestimated? Objects on the manic cusp — strangers in a strange land, foreigners out for a good time — vibrating, fluctuating like the invisible wind. Objects in identity crises — yet absolutely grounded, with a resonant core. They're not a movement, and they're not a category, but each artist has taken upon himself to say that which hasn't quite been said before — and said it in some incredibly quirky ways.